Examples of writing

Inscription of Xi'an Fu

Bilingual particular from the Eastern Syriac inscription of Xi'an Fu (8th century, Tang dinasty).

The very regular estrangelo visible here is written vertically on the right side of the stele: on every column, a clerk’s name is found, together with its Chinese translation.

gygwy qšyš’ w’rkydyqwn

pwlws qšyš’ - seng bao ling

šmšwn qšyš’ - seng shen shen

’dm qšyš’ - seng fa yuan

’ly’ qšyš’ - seng li ben

’ysḥq qšyš’ - seng he ming

Gigoy, priest and archdeacon

Paolo, presbitero - priest - cleric Baoling

Sansone, presbitero - priest - cleric Shenshen

Adamo, priest - cleric Fayuan

Elia, priest - cleric Liben

Isacco, priest - cleric Heming

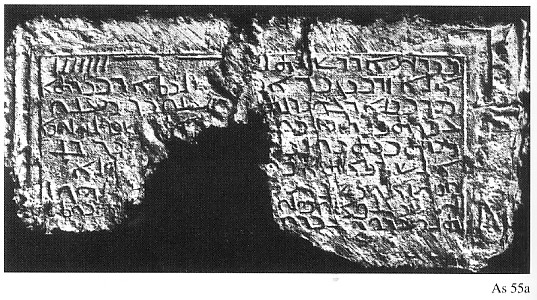

The inscription of Birecik

The earliest Syriac inscription, coming from Birecik (6 CE), on the Euphrates (South-Eastern Turkey).

Birḥ ’dr šnt (317)

’n’ zrbyn br ’b[gr] šlyṭ’ dbyrt’

Mrbyn’ d‘wydlt [br] m‘nw br m‘nw

‘bdt byt qbw[r’ hn’ lnp]šy wlḥlwy’

Mrt byty wlbn[y….] yd kl

’nš dy’t’ b[byt qbwr’] hn’

Wyḥz’ wyšbḥ y[brkwnh ’lh’ k]lhwn

Ḥšy glp’ wslw[k ] ywt[’

Tnw ‘rwh ‘bdw[

In the month of Adar of the year 317

I, Zarbiyan son of Abgar, governor of Birta,

Tutor of ‘Awidallat son of M ‘nu son Ma ‘nu

Made this tomb for myself and for Ḥalwiya

Lady of my household, and for my children… every

One who comes to this tomb

And sees and gives praise, may all the gods bless him.

Ḥaššay the sculptor and Seluk…..

made (it)

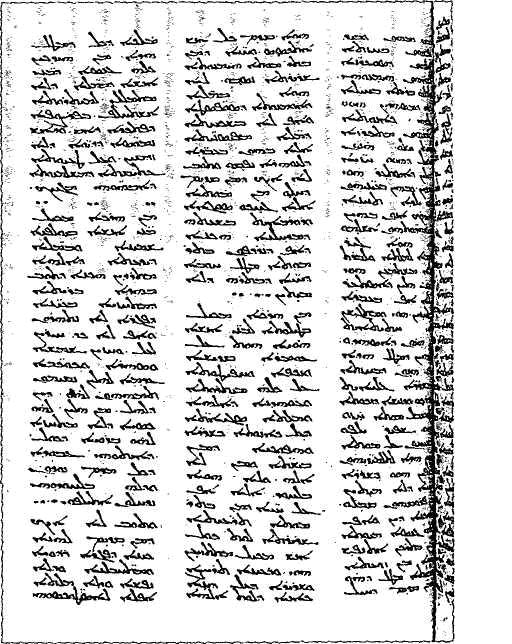

ms BL Add 12150

Example from the first dated manuscript (411 CE), British Library Add. 12150, in estrangelo with occasional cursive variants.

A page from the earliest known example of calligraphic estrangelo on parchment, dated to 411. the manuscripts contains works by Clemens of Rome, Titus of Bostra and Eusebius of Caesarea, and a martyrologion. The text is always written on three columns per page, with an average of 38-42 lines per column. Diacritical signs are still rare.

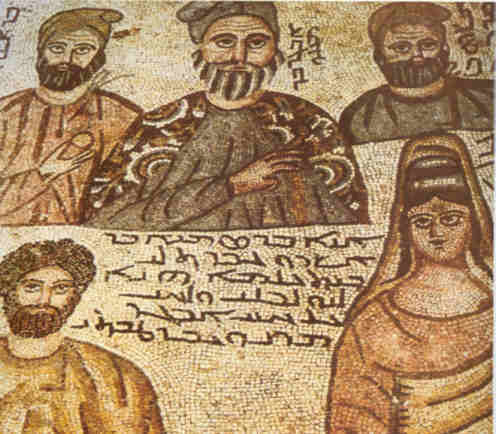

Funerary mosaic

Particular from an Edessene funerary mosaic, the so-called “mosaic of Abgar”, end of the 2nd-the beginning of the 3rd century, found in the northern cemetery of Edessa and presenting an archaic form of estrangelo.

’n’ br smy’ br

’šdw ‘bdt ly

Byt ‘lm’ hn’

Ly wlbny wlḥy

‘l ḥyy ’bgr

Mry w‘bd ṭbti

I, Bar Simya son of

Ašadu, made for myself

This house for ever,

For myself and for my children and for my brothers,

For the life of Abgar,

My lord and benefactor.

The name ’bgr br | m‘nw, “Abgar son of Ma‘nu” is also clearly readable; it is written aside the head of the central feature.

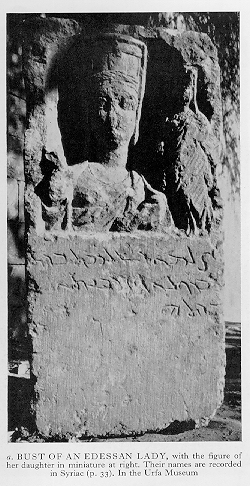

Bust of a woman with daughter

Bust of a woman, found in Edessa, with small figure (whole body) of the woman’s daughter and inscrition in estrangelo. Origin and date unknown.

Ṣlm’ dšlmt brt

Mrwn’ wdrbyt

Brth

Image of Šalmat daughter of

Maruna and of Rabbayta

Her daughter

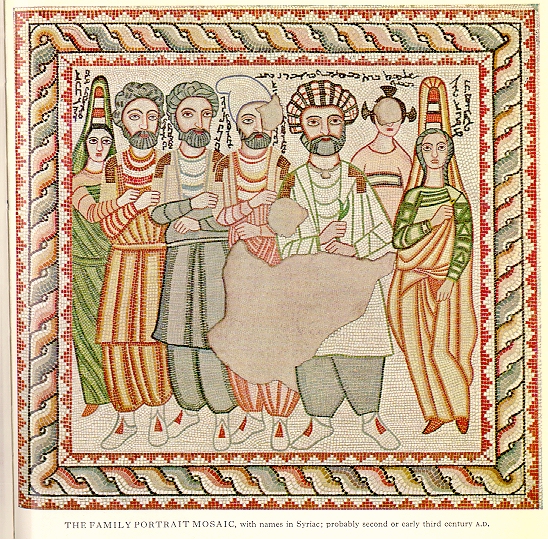

Edessene family - mosaic

Edessene undated mosaic; likely of the 3rd century. It depicts a rich family; the names of the members are written above and between their faces.

G‘w ’ntt

Mqymw

Šlmt brt

M‘nw

Mqymw br ’bdnḥy

’z … br

Mqymw

‘bdšmš br

Mqymw

M‘nw br

Mqymw

’mtnḥy

Brt mqymw

Ga‘u wife

Of Muqimu

Šalmat daughter

Of Ma‘nu

Muqimu

Son of Abdanaḥay

Az … son of Muqimu

‘Abdšamaš son of Muqimu

Ma‘nu son of Muqimu

Amatnaḥay daughter of Muqimu

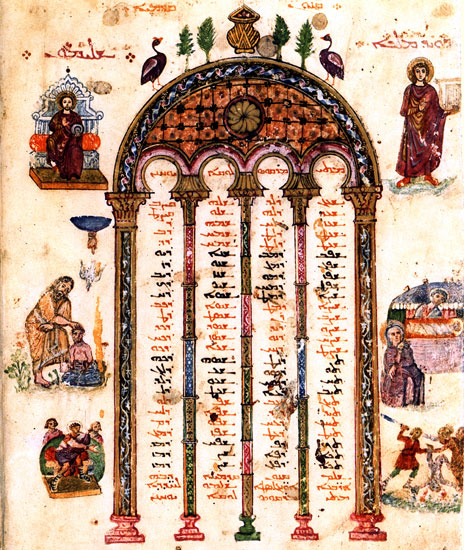

Gospel of Rabbula

An image from the famous Gospel of Rabbula. Handwritten in Manoscritto in estrangelo and copied in 586 at the monastery of John of bet Zagba, north of Apamea, Syria; it is now preserved at the Laurenziana library in Florence, Plut. I. 56.

The manuscript contains the so-called Harmony of the Gospels, which was the work of Tatian (3rd century).

At the head of the page: “first canon” (qnwn qdmy’): i.e. the first of ten tables illustrating the Eusebian canons, which enumerate synoptic passages of the Gospels in order to highlight their agreement.

At the top of the page Solomon (Šlymwn) on the left and king David (Dwyd mlk’), on the right are visible.

In the four spaces of the architectonic element, the numbers which (indicated by means of Syriac letters) denote synoptic passages are set into columns. At the top of each column, the names of an evangelist is found: from left to right, John (Ywḥnn), Luke (Lwq’), Mark (Mrqws), Matthew (Mty). At the bottom, through the last three lines, in red colour: “End of the first canon according to which the four evangelists concord with one another” (šlm qnwn qdmy’ dbh ’rb‘’ ’wnglsṭ’ šlmw lḥdd’). This is followed once again by the names of the evangelists.

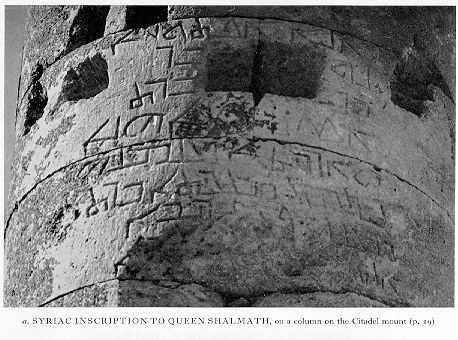

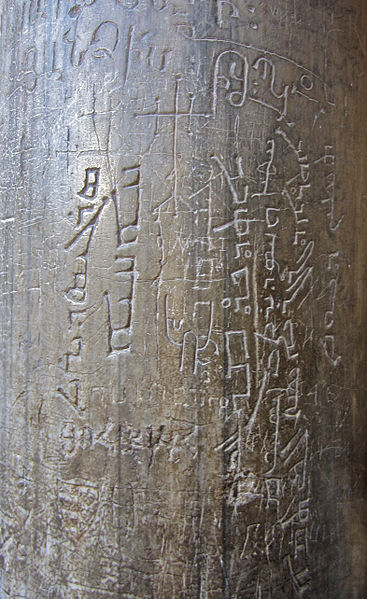

Inscription for Queen Shalmat

Undated inscription on a column, likely of the first half of the 3rd century, coming from the citadel of Urfa (Edessa).

’n’ ’ptwḥ’

Nw[hdr’] br

Brš[….‘]bdt

’sṭwn’ hn’

W’dryṭ’ d‘l mnh

Lšlmt mlkt’ brt

Mn‘w pṣgryb’

’nt[t…….]’

Mrty [w‘bdt ṭbty

I Aptuḥa,

Com[mandant], son of …

Made this column

And the statue above it

For Šalmat, the queen, daughter of

Ma‘nu, the crown prince,

Wife [of….]

my lady [and my benefactor

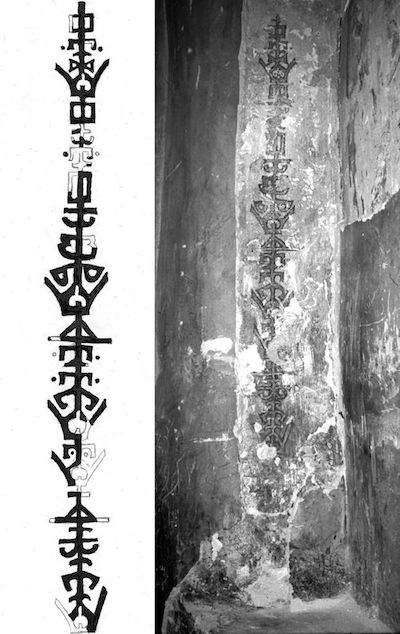

Example of a “mirror inscription” in Syriac

Source: Photo: Karel C. Innemée. Drawing by Lucas Van Rompay. Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute.

The inscription is painted longitudinally on the wall of the main church of the Dayr al-Suryān monastery in Egypt and it contains the name Cyriac, patriarch of Antioch (qryšʾ (sic; qdyšʾ?) qwryqws pʾṭryrkʾ d-ʾntywykyʾ).

Paleographic Tables

Paleographic tables containing a large number of examples of Syriac script can be downloaded here (credits Prof Borbone)

Jerusalem Column inscriptions

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Two among several inscriptions engraved by pilgrims in Syriac on the pillars at the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The first one, in Estrangelo, mentions the name and provenance only: ܣܪܓܝܣ ܕܝܪܝܐ ܚܐܚܝܐ, ‘Sargis the monk, from Ḥaḥ’, a village in Ṭur ‘Abdin, in South-Eastern Turkey; however it was possible to identify this personage thanks to a note he himself wrote in a Gospel book. He is Sargis, metropolitan from Ḥaḥ since 1505, who visited the Holy Sepulchre as a monk in 1490 and in 1502, before rising to his position. Cf. Brock-Goldfus-Kofsky 2007, 417-418. The second inscription, more extended and in mixed Estrangelo and Serto, reads: ܐܬܕܟܪ ܡܪܢ ܠܥܒܕܟ ܚܛܝܐ ܘܢܝܣ ܕܝܪܝܐ ܒܪ ܐܝܣܚܩ ܡܢ ܐܬܪܐ ܕܓܪܓܪܝܐ ܣܢܬ ܐܠܦ ܬܡܐ ܬܣܥܝܢ ܕܝܘܢܐ, “Remember, our Lord, your servant the sinner Wanis (sic) the monk, son of Isaac from the region of the people of Gargar. The year one thousand eight hundred ninety of the Greeks (= 1578/9 d.C.)”. Gargar is a region south of the ancient Melitene, now Malatya. See Brock-Goldfus-Kofsky 2007, 417.

Another unidentifiable name can be read, in smaller Serto, between the two inscriptions: ܓܝܘܪܓܝ, “George”.