Examples of writing

Old Aramaic

Source:

http://www.proel.org/index.php?pagina=alfabetos/arameo

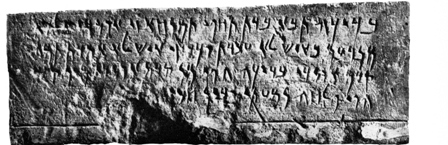

Old Aramaic: Inscription of Bar-Hadad (9th cent. B.C.).

l. 1) nṣb ̓ ٠ zy ٠ śm br[h]

l. 2) dd٠br[ ]

l. 3) mlk ̓rm lmr'h lmlqr

l. 4) t ٠ zy nzr lh wšm ̔ l[ql]

l. 5) h

“Stela which erected Bar-Hadad, son of Atarsamak [...], king of Aram, to his Lord Melqart, who vowed to him and heard his voice”

Votive inscription of king Bar-Hadad, carved under a relief portraying Melqart, Phoenician god of Tyrus. The inscription was unearthed in Brej, North of Aleppo (Syria) and it is housed in the Aleppo Museum. In this text Aramaic script is still very similar, if not identical, with Phoenician script (cf. "Phoenician-Aramaic script", Naveh).

Official Aramaic I

Source:

http://www.proel.org/index.php?pagina=alfabetos/arameo

Official Aramaic: first inscription of Bar-Rakib (second half of the 8th cent. B.C.)

The first inscription of Bar-Rakib was found in Zenjirli (Turkey) in 1891. It is now housed in the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul. The text was carved on a stone (high 1.31 m.; broad 0.62 m.) decorating the new royal palace built by Bar-Rakib, king of Sam ̓al. In the text the latter first protests his loyalty to the king of Assyria, Tiglathpileser III, claiming his legitimacy as son of the former king of Sam ̓al, Panammu (ll. 1-15). In the final lines the building of the new palace is celebrated (ll. 15-20).

Monumental Aramaic script begins in this period a progressive development of the letter forms, leading to a marked difference between Aramaic script and its Phoenician prototypes.

Official Aramaic II

Source:

http://www.proel.org/index.php?pagina=alfabetos/arameo

Official Aramaic: Nerab inscription (7th cent. B.C.)

l. 1) śnzrbn kmr

l. 2) šhr bnrb mt

l. 3) wznh ṣlmh

l. 4) w’rṣth

l. 5) mn ’t

l. 6) thns ṣlm’

l. 7) znh w’rṣt’

l. 8) mn ’šrh

l. 9) šhr wšmš wnkl wnśk ysḥw

l. 10) šmk w’šrk mn ḥyn wmwt lḥh

l. 11) ykṭlwk wyh’bdw zr‘k whn

l. 12) tnṣr ṣlm’ w’rṣt’ z’

l. 13) ’ḥrh ynṣr

l. 14) zy lk

“Sinzeribni, priest of Šahar at Nerab, dead. And this (is) his picture and his tomb. Whoever you (are) who drag away this picture and this tomb from its place, may Šahar and Šamaš and Nikkal and Nusk pluck your name and your place from life and an evil death make you die and may they make your seed come to an end. But, if you protect this picture and this grave, in the future may yours be protected!"

The stela from Nerab (a site south-east of Aleppo, Syria) was found in 1891 and was then moved to the Louvre. The Assyrian style stele portrays a man with upraised hands. The human figure is to be identified with the priest Sinzeribni, quoted in the inscribed text. Lines 1-18 surround the head and the hands of the human figure, while lines 9-14 decorate the lower part of his robe. Monumental Aramaic script shows here the first signs of the influence of contemporary Aramaic cursive script.

Official Aramaic III

Source: J.C.L. Gibson, Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions, II, Oxford 1975, pl. V.

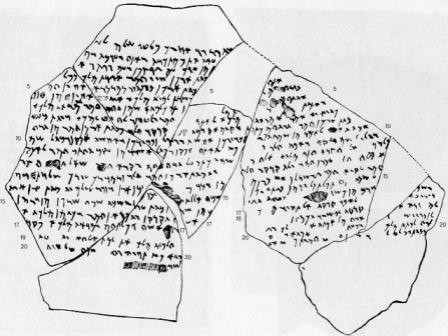

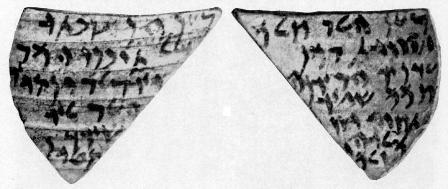

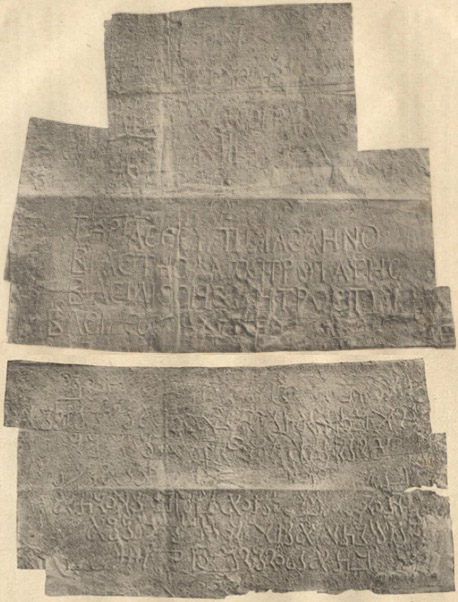

Official Aramaic: Ashur Ostracon (middle of the 7th cent. B.C.)

The Ashur Ostracon is made up of six fragments of potsherd dug out during a series of German archaeological campaigns between 1903 and 1913. The fragments were assembled in Berlin, where they are now housed in the Staatliche Museen. The inscription is written in ink on the external surface of the potsherds. Even though the text is fragmentary and its interpretation quite difficult, it is usually considered as originally divided into two sections. The first section (ls. 1-18) is a letter, sent by the high Assyrian official Bel-etir to his colleague Pir’i-amurri. The letter was written during the period of the rebellion of the king of Babylon, Shamash-shum-ukin, against his brother Ashurbanipal, king of Assyria (about 651-648 B.C.). It is almost impossible to reconstruct the second section (ls. 19-21). It seems that we have here another message of Bel-etir, addressed to another person than Pir’i-amurri.

The Ashur Ostracon is one of the first testimonies of Aramaic cursive script. The latter is very much distinct from the contemporary monumental script. This may be due to the fact that Aramaic cursive script quickly developed in the 7th century B.C., especially in the areas close to the most important political centres. In addition to the modifications of the letter forms, Aramaic cursive in the Ashur Ostracon displays the development of ligatures.

Official Aramaic IV

Source: H. Donner, W. Roellig, Kanaanaeische und Aramaeische Inschriften, III, Wiesbaden 1969, taf. XXXIV.

Official Aramaic: Carpentras inscription (4th cent. B.C.)

l. 1) brykh tb’ brt tḥpy tmnḥ’ zy ’wsry ’lh’

l. 2) mnd‘m b’yš l’ ‘bdt wkrá¹£y ’yš l’ ’mrt tmh

l. 3) qdm ’wsry brykh hwy mn qdm ’wsry myn qḥy

l. 4) hwy plḥh nm‘ty wbyn ḥsyh[y] [...]

“Blessed be Tabi, daughter of Taḥapi, devotee of the god Osiris. Nothing evil she did, no calumny she said against anyone here. Blessed be you before Osiris. Receive water from before Osiris. Be a servant of the Lord of the Two Truths and among the favoured ones [be]”.

The Carpentras inscription was the first Aramaic inscription to be published in Europe. Actually it was dug out in the French town of Carpentras, where it was brought in an unrecorded date. Its discoverer was M. Rigord, who published it in 1704. The text finds its place at the base of a limestone stela where two funerary scenes are carved. The latter are represented according to ancient Egyptian cultural parameters. The language of the text is characterized by the presence of Egyptian names and words and it is set in the framework of Egyptian Aramaic linguistic milieu of the Late Achaemenid period. The script of the Carpentras stela fully demonstrates the deep influence of cursive Aramaic script on monumental Aramaic script in this period.

Official Aramaic V

Source: J.C.L. Gibson, Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions, II, Oxford 1975, pl. V.

Official Aramaic: dream ostracon (late 5th cent. B.C.)

Recto

l. 1) k‘n hlw ḥlm

l. 2) 1 ḥzyt wmn

l. 3) ‘dn’ hw ’nh

l. 4) ḥmm šg’

l. 5) [’]tḥzy ḥz[w]

l. 6) mlwhy l. 7) šlm

Verso

l. 1) k‘n hn ṣbty

l. 2) kl tzbny hmw l. 3) y’klw ynqy’ l. 4) hlw l’ l. 5) š’r

l. 6) qṭyn

Recto

“Now, behold, a dream, one, I saw and from that moment I had a high temperature. A vision appeared, its words: health!”

Verso

“Now, if you sell all my valuables, the children will eat. Behold, not a few rest (should be left).”

The dream ostracon comes from the Elephantine island (Egypt). It was purchased in 1886 and is now in Staatliche Museen in Berlin. The text is written in ink on both sides of the pottery fragment. Even tough difficulties are found in the interpretation of the text, it seems likely that we have here a message sent by an husband to his wife. He is far from home and he has been troubled by dreams. He evidently consulted some expert in oniromancy before writing his message. Aramaic writing on this potsherd well represents Aramaic cursive script of the Achaemenid period.

Official Aramaic VI

Source: E. Sachau, Aramaeische Papyrus und Ostraka, II, Leipzig 1911, taf. 75.

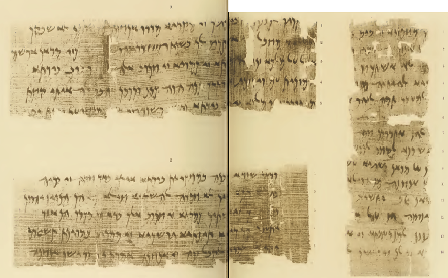

Official Aramaic: Elephantine papyrus (end of the 5th cent. B.C.)

Elephantine island is located in southern Egypt, on the upper part of the Nile. It was the founding place of a large amount of Aramaic papyri. Most of them are connected with the life of a Jewish community of mercenaries, settled there during the 5th century B.C. The papyrus presented here (now in University of Strasbourg, France) contains a letter, addressed to an unknown Persian official, where the Egyptian priests of Khnum are accused of running riot in the Jewish quarter. The papyrus is an excellent testimony of the evolution of Aramaic cursive script even in an area far away from the main centres of Achaemenid supremacy.

Middle Aramaic I

Source:

http://www.proel.org/index.php?pagina=alfabetos/nabateo

Middle Aramaic: Nabataean inscription from Turkmaniyyah (about 50 A.D.)

The inscription of Turkmaniyyah is found in the site of Qabr at-Turkmaniyyah (Petra). This tomb inscription does not contain any information as far as the name of the owner or the donor and the date of building are concerned. The dating of the text was thus reached thanks to palaeography. The Nabatean Aramaic script is presented here in mature, fully developed forms.

Middle Aramaic II

Source: Hatra. Città del Sole. Catalogo della Mostra, Torino 2000, p. 22.

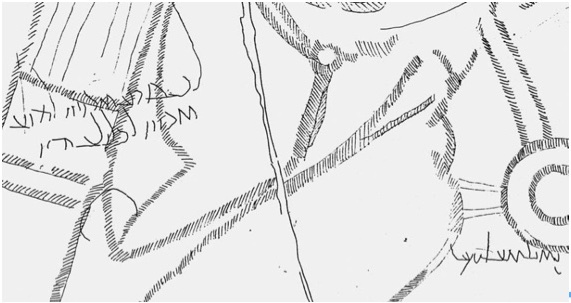

Middle Aramaic: Hatran inscriptions (middle of the 2nd century A.D.)

Inscription H 106a

l. 1) grgn ’bšp’

l. 1) Gorgone, ’Abšpē.

Inscription H 106b

l. 1) [z]bydw wyhbšy

l. 2) [bn’] brnny ’rdkl’

l. 3) br yhbšy ’rdkl’

l. 4) dy ’lh’ bḥlm’

l. 5) ’lp hnw

l. 1) Zobedu and Yhabšay

l. 2) sons of the architect Barnannay

l. 3) son of the architect Yhabšay,

l. 4) whom the god in dream

l. 5) taught to.

Both inscriptions are found on the façade of the main sanctuary of the city of Hatra (North-western Iraq). The first text describes a Gorgon relief carved nearby. The relief has an apotropaic function. The second text in its turn refers to the two architects involved in the building of the temple (Great Iwans), dedicated to the cult of the Sun god. Both texts are good representatives of monumental Hatran Aramaic script.

Middle Aramaic III

Source:

http://www.proel.org/index.php?pagina=alfabetos/arameo

Middle Aramaic: Palmyrene inscription (Palmyra, 3rd cent. A.D.)

1) ṣlmt sp ṭmy’ btzby nhyrt’ wzdqt[']

2) mlkt’ sp ṭmyw’ zbd’ rb ḥyl’

3) rb’ wzby rb ḥyl’ dy tdmwr qr ṭs ṭw'

4) 'qym lmrthwn byr ḥ'b dy šnt 5 x 100 + 80 + 2

1) Statue of Septimia Batzabbay (Zenobia), the illustious and righteous

2) queen. The Septimii: Zabda, commander in chief

3) and Zabbay, commander of Palmyra, the most excellent (plur.),

4) set up for their lady. In the month of Ab of the year 582.

This dedication, together with its Greek parallel text, is still found in the Grand Colonnade in Palmyra (Syria). According to the text, it dates back to 271 A.D. (year 582 in the Seleucid era). In this artifact, Palmyrene script typical of official inscriptions reached a full development.

Middle Aramaic IV

Source:

http://www.proel.org/index.php?pagina=alfabetos/elimaico

Middle Aramaic: legend on a coin issued by the king of Elymais Kamnaskires Orodes (Elymais, end of the 1st cent. A.D.)

kbnškyr wrwd mlk’ br wrwd mlk’

"King Kamnaskires Orodes, son of King Orode"

During the 1st century A.D. a peculiar form of Aramaic script began to be used for coin legends in the kingdom of Elymais (Khuzistan, Iran, 2nd cent. B.C. - 3rd cent. A.D.). This script belongs to the South-mesopotamian branch of Oriental Aramaic scripts and was also employed in official inscriptions on rock-sculptures.

Middle Aramaic V

Source: M. Moriggi, ‘Varia Epigraphica Hatrena’, Parthica 12 (2010), p. 74 (fig. 5).

Hatran graffiti (second half of the 3th cent. A.D.)

Inscription H 1060

l. 1) lbyš (ʾhl d...) lmzʾ

l. 2) (hdy...) (lb...)

l. 1) Clothed, of the lineage (?) (...) for hair (?)

l. 2) (...)

Iscrizione H 1059

l. 1) yhblhʾ lṭbʾ

l. 1) yhblhʾ for good!

Besides the Hatran writing system, used on monuments and, more generally, in official contexts, graffiti and painted inscriptions were discovered in domestic contexts, such as the one from which originated the two texts shown. Both were engraved on the roughcast of Building A, a private residential building in the city, unearthed by the Italian Archaeological Mission at Hatra (Turin). The Hatran Aramaic writing system in these documents presents unattested forms of the typology “monumental”. Ligatures between graphemes, usually unforeseen in the Aramaic writing systems of Northern Mesopotamia of that time can also be noticed.

Middle Aramaic VI

Source: C. Clermont-Ganneau, ‘Odeinat et Vaballat: rois de Palmyre, et leur titre romain de corrector’, Revue Biblique 29 (1920), pp. 392-393

Latin and Greek sections above and Palmyrene Aramaic section below

Latin text

DN / AVR VAL DIOCLE / V [...] CO(L) PAL / XIII

D(omino) N(ostro) / Aur(elius) Val(erius) Diocle(tianus) / V [...] Co(lonia) Pal(myra) / XIII

Greek text

l. 1) [...]

l. 2) [...κ]α[ὶ ὑπὲρ σω-]

l. 3) τηρίας Σεπτιμίας Ζηνο-

l. 4) βίας τῆς λαμπροτάτης

l. 5) βασιλίσσης μητρὸς τοῦ

l. 6) βασιλέως, [...] υ[...]

l. 1) [...]

l. 2) and for the salva-

l. 3) -tion of Septimia Zeno-

l. 4) -bia, the renowned

l. 5) queen, mother of the

l. 6) king [...]

Palmyrene Aramaic text

l. 1) ʿl ḥ[ywhy] wz[kwth dy] spṭymyws

l. 2) whblt ʾtndr[ws nhy]rʾ mlk mlkʾ

l. 3) wʾpnrtṭʾ dy mdnḥʾ klh br

l. 4) spṭ[ymy]ws [ʾdynt mlk] mlkʾ wʿl

l. 5) ḥyh dy spṭymyʾ btzby nhyrtʾ

l. 6) mlktʾ ʾmh dy mlk mlkʾ

l. 7) bt ʾnṭywkws m 10+4

l. 1) For the life and victory of the illustrious Septimus

l. 2) Whblt Athenodorus, king of kings

l. 3) and Corrector Totius Orientis, son of

l. 4) Septimius Odaenathus, king of kings and for

l. 5) the life of the illustrious Septimia Btzby,

l. 6) the queen, mother of the king of kings,

l. 7) daughter of Antiochus. Mile 14

The inscription, unearthed west of Palmyra, shows the coexistence of Aramaic Palmyrene writing system and Greek and Latin writing systems on the same monument. The Greek and the Aramaic texts date back to the period in which Palmyra, having asserted independence from Rome, was ruled by Septimius Odaenathus and by Zenobia, who claimed for themselves and for their successors the dignity of a king of the East. The text dates back between 268 and 270 A.D. The Latin text was added later, although originally the support on which the inscription was carved had probably been employed as a milestone.

Late Aramaic I

Source:

http://www.schoyencollection.com/aram-heb-syr2.html

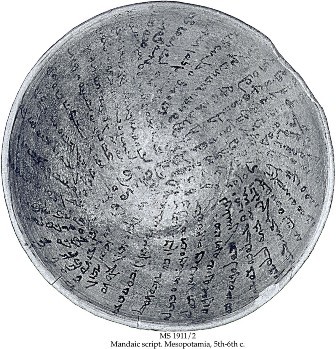

Late Aramaic: incantation bowl inscribed with a Mandaic text (5th-6th cent. A.D.)

The inscription written on this bowl, as well as many others, contains a protective exorcism, aimed at driving away evil spirits from the house of Nanai and Ihana, who ordered the bowl. Mesopotamian incantation bowls are the earliest testimonies of Mandaic language and script. The Mandaeans were a gnostic sect settled in southern Mesopotamia, where their descendants still live. Mandaic script could have been developed from the Aramaic scripts used in the chanceries of the kingdoms of Elymais (2nd cent. A.D.) and Carachene (3rd cent. A.D.). The Mandaic script is characterized by a cursive, systematically ligatured ductus.

Late Aramaic II

Source:

http://www.schoyencollection.com/aram-heb-syr2.html

Late Aramaic: incantation bowl inscribed with a Syriac text in proto-Manichaean script (5th-6th cent. A.D.)

Incantation bowls are a precious tool to investigate written non-literary varieties of Late Aramaic. As a matter of fact Syriac incantation bowls display a series of linguistic traits not attested to in the contemporary and later literary varieties of Syriac. Two scripts are employed in the Syriac bowls: estrangela and “pre-” or “proto-Manichaean” script. The latter is a forerunner of the later “Manichaean” script, used in Manichaean manuscripts of Central Asia (9th-10th cent. A.D.). See the section “Aramaic script in Iran and Central Asia”.

Late Aramaic III

Source:

https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~jtreat/rs/002/Judaism/talmud.html

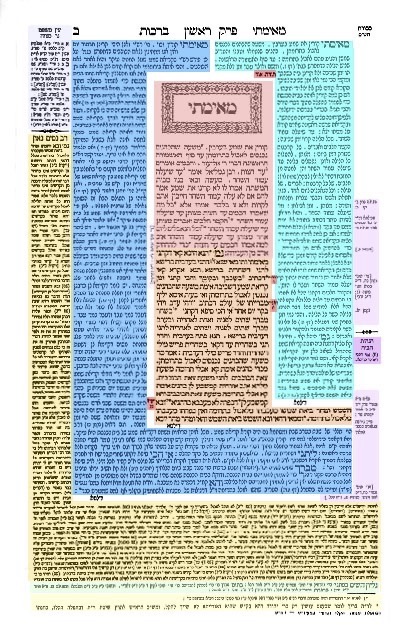

The Aramaic square script, still in use today for annotating modern Hebrew, is used in this Talmudic page in order to render both the Mishnah text (in Hebrew, highlighted in pink in the central column) and the Gemara text (in Aramaic, highlighed in orange immediately below).

Aramaic script and Iranian languages

Source: E. Morano, 'L'uso della scrittura tra i popoli iranici: dal cuneiforme all'adattamento delle scritture semitiche' in La scrittura nel Vicino Oriente antico. Atti del Convegno Internazionale. Milano, 26 Gennaio 2008, Milano 2009, p. 126 (fig. 3).

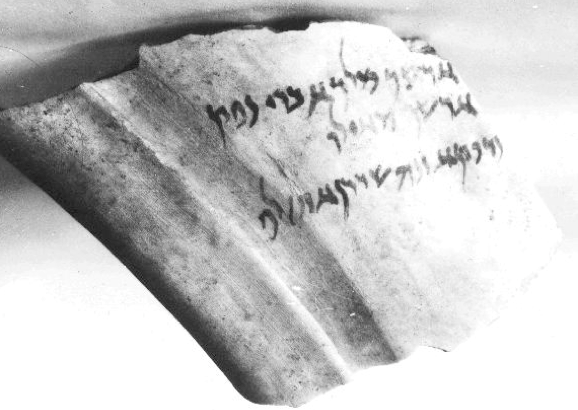

Aramaic script and Iranian languages: ostracon from Parthian Nisa (1st cent. B.C.)

l. 1) ’ršk MLK’ BRY npt

l. 2) ’ršk Q’YLw

l. 3) NDBT’ ZNH Š‘RN’ 2 x ’LP

l. 1) The king Arsaces, son of the nephew

l. 2) of Arsaces. Registered

l. 3) this offer of 2000 epha of barley.

Even though the adoption of Aramaic script in Iranian linguistic environment took place during the Achaemenid period (6th-4th cent. B.C.), the first written documents of an Iranian language (Parthian) put down in an Aramaic script derived from Achaemenid Aramaic prototypes date from the beginning of Parthian period (2nd-1st century B.C.). Many Parthian economical texts written in Aramaic script were found in the old Parthian capital Nisa (Turkmenistan). In the ostracon presented here Aramaic heterograms are transcribed in capital letters.