- Introduction

- Index

- Further information

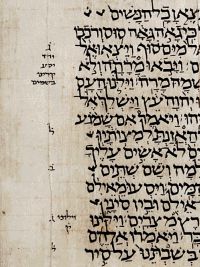

Of Phoenician origin and alphabetic nature, Hebrew is composed of 22 consonant signs, and is read from right to left.

Go to the online resources.

Online resourcesIndex

I. The origins

From the first half of the 8th century BC to the first quarter of the 6th century BC a writing system that could be said to be certainly and specifically “Hebrew” – that is, first used to transcribe the dialectal variations of the common Canaan language of the peoples living in the central plateaus and the mountains of Judah beginning in the 12th - 11th centuries BC – appeared and began to spread. This usage coincided with the period that goes from the emergence of the independent reigns of Israel, first and subsequently of Judah, and it would remain linked to these reigns until the Assyrian conquest of Samaria, capital of Israel (722 BC) and the Babylonian deportation which overturned the political leadership of Judah (587/586 BC). Given our current knowledge, in fact, it is still harshly debated how to qualify the ‘Izbet Sarta (12th-11th century BC) and Tell Zayit (10th century BC) alphabets, the ostrakon from Khirbet Qeiyafa (10th century BC) and the Gezer (10th-9th century BC) calendar (Phoenician? Late Canaanite? Proto-Hebrew?).

Strong formal resemblances – marked by barely-perceptible local variants – with Phoenician, and consequently with other Canaanite writing systems (Moabite, Ammonite, Edomite, Philistine) indicate that the common historical and geographic origin of these writing systems can be traced to the domination of the Phoenician language in general and the dialect of Tyre in particular in the Canaan region from the 11th century to the first half of the 8th century BC (G. Garbini). In Is. 19:18 the language of the reign of Judah is defined tout court as “śpt kn‘n”, literally “Canaan lips” as evidence of a similar awareness in the speakers themselves. In the south, the tendency to write some signs (k, m, n, p) obliquely, with a rounding off of the vertical line towards the left, is more accentuated than in the Phoenician writing or in the epigraphic evidence from the reigns of Israel and Moab where it was just beginning to appear. This tendency indicates the existence of a widespread scribal tradition and the development and influence of cursive writing. From the 9th century BC, in the wake of the new policy of Assyrian expansion, the first elements of the attendant cultural pressure of Aramaic can be seen in the influence which Aramaic writing had on the variants, including “Hebrew”, of the Phoenician alphabet used throughout southern Palestine. This influence accounts for the appearance – in end as well as mid positions – of the first matres lectionis, i.e., the use of consonant signs for the sounds ’ , w and y, the last two in particular, as the transcription not so much or only of semivowels in non-contracted diphthongs, as of full vowel sounds (a, o/u, e/i).

The uses are limited to wall graffiti, monumental inscriptions and vase paintings or engravings, letters and seals on ostraka in the territories of the reigns of Israel and Judah.

“Alphabet, Jewish” entry of the Jewish Encyclopedia, table 1, columns 3-4.

II. From Babylonia to the second revolt against Rome: developments and ideologies

With the return over 150 years (539 – 398 BC) from Babylonia to the new Persian province of “Yehud”, the influence of Aramaic became ever stronger and more massive. This influence of Aramaic – which had by now become the new lingua franca of the Near East and was destined to become the common spoken language in Palestine – was such that the Phoenician characters were completely assimilated into Aramaic writing (cf. Jewish Encyclopedia, ibid., table 2).

The archeological findings in the sites of Elephantine, in the south of Egypt near the borders with Nubia, and of Khirbet Qumran, Masada, Murabba‘at, Khirbet Mird, Naḥal Ḥever, Naḥal Mishmar and Wadi ed-Daliyeh (north of Jericho), in the desert of Judea around the Dead Sea (see map with some of the sites cited), have brought to light literary texts and non-literary documents on papyrus and/or parchment, private letters and ostraka in both languages dating to the period from the 5th century to the last Jewish revolt of 132-135 AD. In this period the use of the matres lectionis was further developed and confirmed.

Phoenician writing was conserved sporadically and schematically in a few Hebrew manuscripts from Qumran and in some Greek papyri from Naḥal Ḥever (in particular, to write the tetragrammaton YHWH), and on coins, as an ideological sign of the re-found independence and of the new flowering of the reign of Israel under the Hasmoneans (143 – 63 BC), but it had disappeared by 1st century AD. Curiously, it reappeared only in the mint marks coined at the time of the two great Jewish revolts (66-70 AD and 132-135 AD) in the light of the first temporary successes (cf. Jewish Encyclopedia, ibid. table 1, columns 5-7). It survives today in the Samaritan alphabet, with some modifications in the uncials (cf. Jewish Encyclopedia, ibid. table 1, columns 8-9).

III. Towards the medieval and modern eras: square, cursive and special scripts

The further evolution of the new type of alphabet, called “square” due to the straight and square form of its letters, developed beginning from 6th-8th century AD. The manuscript transmission (Masorah) of the “canonical” texts of the Jewish religious tradition (Tanakh; Mishnah; Talmudim) is based on these new developments. Vocalization by matres lectionis has been replaced by complex, geographically differentiated systems of vocalization marked by punctuation: the Tiberian, which will prevail, the Palestinian, the Babylonian, and the Samaritan, considered heterodox by “official” Judaism.

At the same time, in the Jewish communities of the Diaspora, throughout the Mediterranean region and the Arabic peninsula, in continental and Eastern Europe, cursive writing and special scripts for glosses and comments on the new “canon” were beginning to develop (cf. Jewish Encyclopedia, ibid. table 4 and 5).

Square writing and one of its cursive variants, of Ashkenazi origin, are still officially in use in the State of Israel and in the literary production in Modern Hebrew or Ivrit.

Photo Gallery

List of symbols

Examples of writing

Bibliography

Map of places