Examples of writing

Inscription from Tel Zayit (10th century BC)

(from right to left): W H Ḥ Z T

Found on the wall of a building in Tel Zayit, in Judea south of Jerusalem, the inscription is an alphabetic sequence. Four consonants (W and H and Ḥ and Z) are inverted compared to their usual order. It’s difficult to establish if the writing is Hebrew, considering the date of the inscription and the historical and archeological problems of the existence and extension of a united Israelite reign or even, possibly, of the sole reign of Judah in that period.

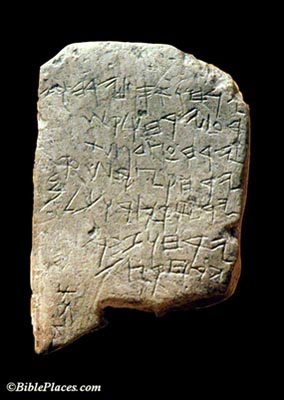

Gezer Calendar (10th - 9th century BC)

(Image from BiblePlaces.com)

L. 1: YRḤW ’SP | YRḤW Z

L. 2: R‘ | YRḤW LḲŠ |

L. 3: YRḤ ‘SD PŠT

L. 4: YRḤ ḲṢR Š‘RM

L. 5: YRḤ ḲṢR WKL

L. 6: YRḤW ZMR

L. 7: YRḤ ḲṢ

(vertically, at the end): 'BY

"The months of harvest

the months of sowing

the months of late sowing (?)

the month of cutting the flax

the month of barley harvest

the month of the harvest and of reckoning (?)

the months of grape harvest (?)

the month of summer fruit

Abi... (?)"

The archaic linguistic characters of the inscription (absence of article and w suffix) lead scholars to believe that it is neither Hebrew nor Phoenician. Other hypotheses to identify it range from Philistine origin to a late example of the Canaanite language. The text seems related to a farming culture, but it is not very clear.

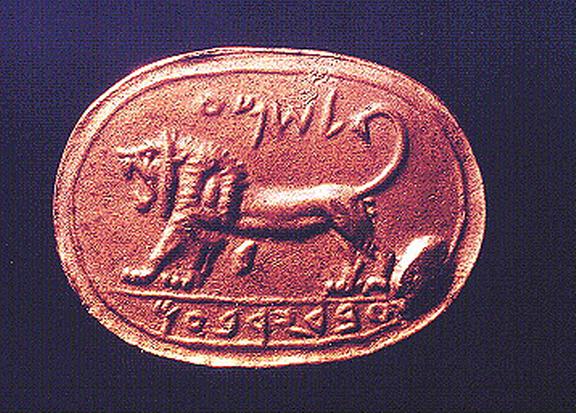

Seal of Šm’ servant of Yrb’m (first half 8th century BC)

L. 1: LŠM‘

L. 2: ‘BD YRB‘M

"(belonging) to Šm' servant of Yrb'm"

The seal was found at Megiddo, in Galilee, at the beginning of the 20th century. The incision of the lion allows it to be dated as not before the 8th century. The name Yrb'm can therefore only refer to Jeroboam II, last great sovereign of the reign of Israel from about 788 to 747 BC.

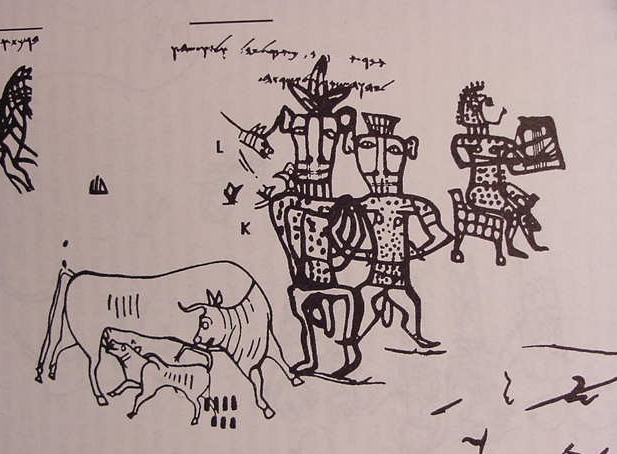

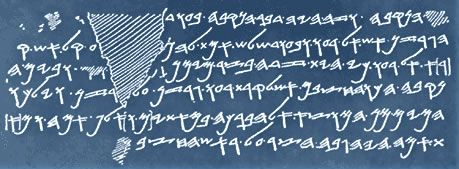

Drawing and inscription from pithos A of Kuntillet `Ajrud (first half 8th century BC)

The drawing was found on the ceramic fragments of a pithos that came to light among the ruins of Kuntillet `Ajrud (caravanserai? fortress? religious center?) in the Sinai desert, during the 1975-1976 excavations. The inscription over the head of the human figure reads:

L. 1: ’MR ’[ŠYW] H[ML]K. ’MR LYHL[L’] WLY‘WŠH W[ ] BRKT ’TKM

L. 2: LYHWH ŠMRN WL’ŠRTH

"Says ’[šyhw?] [the king?]: say to Yhl[...] and to Yw‘šh and [...] I bless you

on behalf of Yhwh of Samaria and of his Ašerah"

For a detailed interpretation of the text and images, see here [article in Italian].

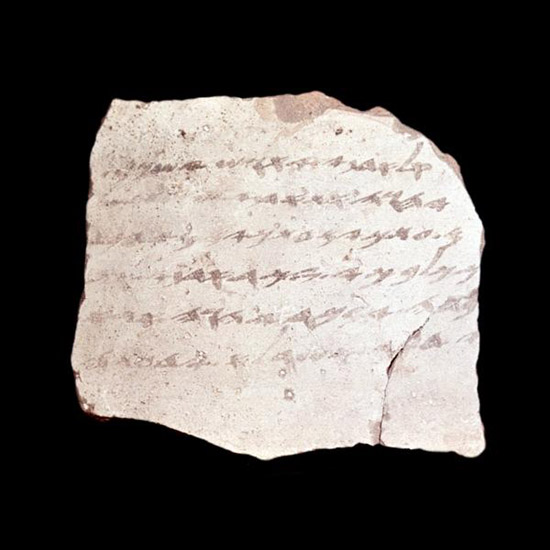

Ostrakon of Samaria (about 850-750 BC): image and paleography

Found in 1910 in an annex building of the Royal Palace of Samaria, capital of the Northern Reign, the 100 (about) ostraka are receipts for the transport of oil and wine, from the royal lands (krm, vineyard, or gt, enclosed garden) to the palace. The highest year cited in the initial formula is 17, so these ostraka can be ascribable to only three reigns: Achab, in the 9th century (improbable), Jehoash, or his son Jeroboam II, in the 8th. These receipts, together with the finding of tableware vases in the Phoenician style and of furnishing plates in ivory, also in the Phoenician style but with Egyptian decorations, indicate the economic development reached in the Northern Reign in the shadow of the Assyrian Empire, before the capitulation (722). This means they represent first-hand sources which integrate the oracles of Amos (cf. Am 5:11; 6:4-6; 8:4-6) and Hosea (cf. Hs 12: 2), datable to the same period.

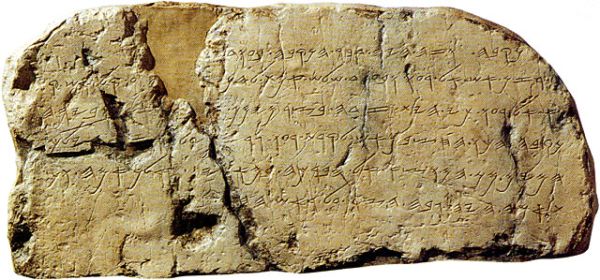

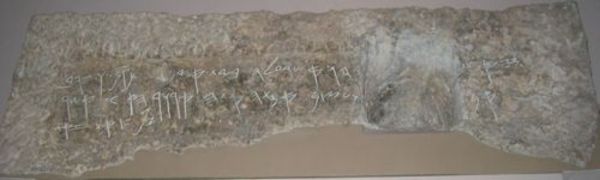

Paleo-Hebrew writing from the Siloam Canal (Jerusalem, second half 8th century BC)

Found in 1880 in loco in Jerusalem, the Siloam inscription describes the last stages of the excavations in the rock of an aqueduct: the first voices that each of the teams of excavators hears coming from the opposite direction is followed by the arrival of the canalized water. The correspondence with the literary texts which refer to similar works at the time of Hezekiah (cf. 2Kgs 20:20 and 2Chr 32:30) have led scholars to believe that the inscription reproduces a commemorative text written for the occasion, in prevision of and in concomitance with the siege of Sennacherib in 701 BC (concerning his failed expeditions against the reign of Judah and Egypt, see the versions offered by 2Kgs 18:13 – 19:37 and 2Chr 32:1-23, on one hand, and Herodotus, The Histories, Book II, 141: 2-5, on the other). The official nature of the inscription is, however, still being discussed.

Transcriptions and translation of the inscription of the Siloam canal

“HNḲBH WZH HYH DBR HNḲBH B‘WD [......]

HGRZN ’Š ’L R‘W WB‘WD ŠLŠ ’MT LHN[......]‘ ḲL ’Š Ḳ

[R]’ ’L R‘W KY HYT ZDH BṢR MYMN W […]L WBYM H

NḲBH HKW HḤṢBM ’Š LḲRT R‘W GRZN ‘L[G]RZN WYLKW

HMYM MN HMWṢ’ ’L HBRKH BM’TY[M W]’LP ’MH WM[’]

T ’MH HYH GBH HṢR ‘L R’Š HḤṢB[M]”

“... the tunnel ... and this is the story of the tunnel while ...

... the axes, each crew towards the other and while three cubits were left to cut ... the voice of a man called ...

to his counterpart, for there was breach in the rock, on the right ... and on the day of the

tunnel (being finished) the stonecutters struck each man towards his counterpart, ax against ax and flowed

water from the source to the canal for 1200 cubits. and 100

cubits was the height over the head of the stonecutters ...”

(Cf. 2Kgs 20: 20 and 2Chr 32:30)

Seal of 'Sn' (8th century BC)

L’SN’

"(Belonging) to ’sn’"

Made of white and brown agate, this egg-shaped seal was probably engraved in a ring. It dates back to Hezekiah's kingdom (8th century BC) and clearly shows the influence of Egyptian iconography, thus reinforcing the evidence for the growing proximity, both political and cultural, between Judah and Egypt against Assyrian expansion.

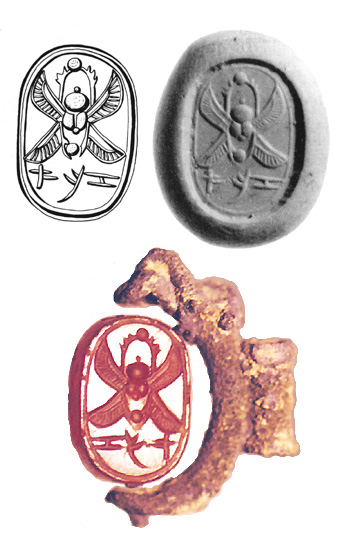

Seal of Zk' (late 8th century BC)

"ZK’"

"Zk’"

Made of red carnelian, the seal is set in a silver pendant. The four-winged scarab, of evident Egyptian influence, was a common motif in western Semitic glyptic. The two-winged one, in particular, seems to have been the royal emblem of Hezekiah, as can be seen in impressions of his seals.

Seal of Ḥbrn (late 8th century BC)

(top): LMLK

(bottom): (Ḥ)BRN

"(Belonging) to the king; (from) Ḥbrn"

Traditionally dated to the end of the 8th century, this seal is part of a series found in Lachish and originating from Soko, Zif and from an otherwise-unknown Mmst (Emmaus, modern Amwas? Another name for Jerusalem?) All have been pressed into the fresh clay of some jar handles before the jars were baked. The emblems alternate among the sun, the solar disk with two wings, and a scarab with for wings; this last was perhaps a symbol from the royal house of Judah. If the dating is correct, the reference to the king would refer back to Ezekiah (727-698 BC). Various hypotheses have been forwarded about the use of the jars, for example that they contained products from the lands of the king (cf. 2 Cr 32:28), or, alternatively, that they were used as containers for the taxes and the distribution of foodstuffs, or that the seals simply indicated the origin of the jars from the workshops of the palace. In any case, it is fairly probable that their production took place during the economic and bureaucratic organization which the reign of Judah endured after the rebellion against the Assyrians (cf. as well the inscription of the Siloam canal).

Funeral inscription of a royal official (Silwan, near Jerusalem; end 8th century BC)

L. 1: Z’T [...Y]HW ’ŠR ‘L HBYT ‘YN [BH?] KSP W[Z]HB

L. 2: [KY?] ’M [...] [W]‘ṢM ’MTH ’TH ’RWR H’[..] ’ŠR

L. 3: YP[TḤ] ’T [H]Z’T

"This [(is the tomb of) ...y]hw, superintendent of the palace. There is no silver or gold in it

but only [his bones?] [and] the bones of his servant with him. Cursed [he?] who

opens it"

The inscription was found in Silwan (Shiloah), south-east of Jerusalem in 1870, but was only deciphered in 1953 due to the deterioration of the letters. The epigraphy originally formed the architrave of a tomb dug in the stony slope of the Kedron Valley. Considering it paleographically, it can only be dated between the end of the 8th and the beginning of the 7th century BC. The buried individual was the superintendent of the palace, a role that had developed over the centuries from administrator of the palace (1 Kings 4:6 and 16:9) to official with political responsibilities (1 Kings 18:3-4) and, lastly, by the 7th century, to vizier of the reign (2 Kings 10:5, 15:5; 18:18, 19:2). Only the final letters of the name are conserved, certainly the theonym –yhw (YHWH). The most probable candidate for the identification is Shebna, who held this office under Hezekiah (727-698 BC), and who was bitterly criticized by the prophet Isaiah exactly because he had dug a tomb in the rock (Is 22:15-25). The inscription would thus bear the long form of the name, as can be seen on ostraka of the same period and in the Hebrew text of Neh 9:4. The mention of a female slave (his wife?) buried with him is of particular interest, as is the reference to the absence of gold and silver, and the curse on anyone who might desecrate the sepulcher: a simple defense against theft (cf. the Phoenician inscriptions of Tabnit and Batnoam between the 5th and 4th centuries BC) or also a deterrent against evidently common “magical” practices (cf. the sepulchral graffiti of Khirbet el-Qom, in Judah, after the end of the 8th century BC and the north-Arabic wall inscription of Bahani between the 5th and 4th centuries BC)?

Letter 18 from ‘Arad (end 7th century BC)

L. 1: L’DNY ’LY

L. 2: ŠB YHWH YŠ

L. 3: ’L LŠLMK W‘T

L. 4: TN LŠMRYHW

L. 5: (written sign for the letek measure) WLḲRSY

L. 6: T TN (written sign for the homer measure)WLD

L. 7: BR ’ŠR Ṣ

L. 8: WTNY ŠLM

L. 9: [B]BYT YHWH

Back:

L. 10: H’ YŠB

"To my Lord ’ly

šb. May YHWH take care

of your prosperity. And now

give to Šmryhw

a letek measure, and to Qerosita

you will give a homer measure.

About the matter which you

ordered of me, everything has been done:

in the house of YHWH

(back) he sits"

The inscription, found in the fortified citadel of ‘Arad (modern Tel ‘Arad) in eastern Negev, is part of a small 'archive' of eighteen documents dealing with a certain Elyašib, perhaps the administrator or military commander of the fortress. They are mostly requests of supplies (wheat, flower, oil, wine) for the troops stationed in the garrison, among whom there were probably also Greek - or from the Aegean islands (Ktym) - mercenaries. Whether the temple of YHWH mentioned in the text is actually the one in Jerusalem or whether it should be identified with the cult building which came to light in loco, provided with altars for the incense and with two monolithic stele or maṣṣebot, is still being animatedly discussed.

Lachish Letter II (589-587 BC)

L. 1: ’L ’DNY Y’WŠ YŠM‘

L. 2: YHWH ’T ’DNY ŠM‘T ŠL

L. 3: M ‘T KYM ‘T KYM MY ‘BD

L. 4: K KLB KY ZKR ’DNY ’T [‘]

L. 5: BDH Y[B]KR YHWH ’[T ’]

L.6: Y D[BR] ’ŠR L’ YD[‘TH]

"To my lord Y’wš. May

YHWH cause my lord to hear news of peace

Even now, even now. Who (is) your servant,

(but) a dog, that my lord should remember

his servant? YHWH give a sign soon (?); there is (?)

nothing you do not know"

In 1935, eighteen inscribed pottery fragments were found in Lachish (modern Tell el-Duweir), bearing the correspondence between the commander of the garrison stationed in that fortified city, and his subordinates. The layer of earth where they were found shows signs of destruction and fire which can be associated with the Babylonian military actions of 587-586 BC. The ostraka, all of which can be dated to the end of the first fifteen years of the 6th century BC, thus document the final days of the Jewish fortress under siege by the forces of Nebuchadnezzar II. The last two lines of Letter II, reproduced here, are difficult to read and interpret. The translation is therefore conjectural in some parts, and follows one of the many suggested reconstructions. The expression of ll. 3-4 “Who is your servant, if but a dog, that...” finds a precise comparison in 2 Kings 8:13 and less precise parallels in 2 Sam 9:8 and 16:9.

Nash Papyrus (150-100 BC)

The Nash Papyrus, oldest document known in Hebrew square script until the Qumran was found in 1947, was purchased in Egypt in 1898 and consists of four fragments which bear the Ten Commandments followed by the prayer “Listen, O Israel”. The text of the Ten Commandments combines the versions of Ex 20:2-17 and Deut 5:6-21. The document presumably originated in Egypt since the expression “house of slavery” in reference to Egypt is omitted. Other discordances between the two passages and the Masoretic Text have been found. The textual particularities of the papyrus reflect, in all probability, its liturgical use, or perhaps its use in private prayer practices.

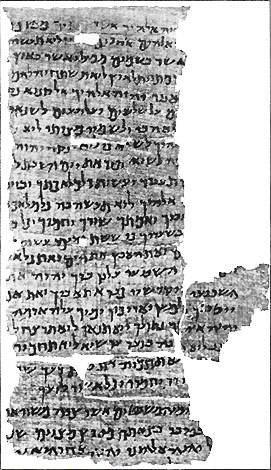

1QIsab (= Is. 57:17 - 59:9; prior to 100 BC)

Perhaps already discovered in the 9th century AD, forgotten and then once again found in 1947 in some grottos near the Dead Sea, the Qumran scrolls have revolutionized our knowledge of every aspect of Judaism in the Palestinian area from the 2nd century BC to 1st century AD. Here above there is one of the earliest specimens of the Biblical book of Isaiah, and below a section of the interpretation, or pešer, of the book of Habakkuk, an interpretation unknown before the discoveries of last century. The writing shows the evolution of the paleo-Hebrew script towards the Hebrew square script of the late ancient period.

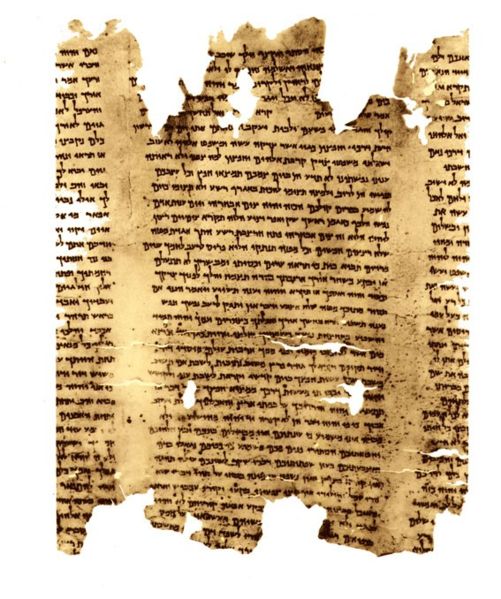

Qumran Hebrew: pesher from Abacuc (end 1st century BC)

LHYWT ’BNYH B‘ŠḲ WKPYS ‘ṢH BGZL W’ŠR (1QpHab col. X l.1)

Interpretation of Hab 2:11: “to be the stone of oppression and the beam made of the woodwork for the robbery, and that which (he said/says)”; the citation of Hab 2:10 follows.

Half shekel (second year of the revolt = 67-68 AD)

Recto: ḤṢY HŠḲL - Š(NT) B

Verso: YRŠLYM HḲDŠH

Recto: "Half shekel" - "Year 2"

Verso: "Holy Jerusalem"

This one and the following two are silver coins minted during the two Jewish wars, the first and second coins during the first war, the third one during the second war. Under Roman rule, minting coins, and even more, silver coins, was a privilege of free cities. It must be added that the first and third coin are clearly roman coins minted anew: the ideological message couldn't have been more dramatically expressed. The inscription in the old Hebrew alphabet stresses the point, if there was any need.

Shekel (fourth year of the revolt = 69-70 AD)

Recto: ŠḲL YSR’L Š(NT) D

Verso: YRŠLYM HḲDŠH

Recto: "Shekel of Israel" - "Year 4"

Verso: "Holy Jerusalem"

Silver Zuz (coin) (134-135 AD)

Recto: ŠM‘N

Verso: LḤRWT YRŠLYM

Recto: "Simon"

Verso: "For the freedom of Jerusalem"

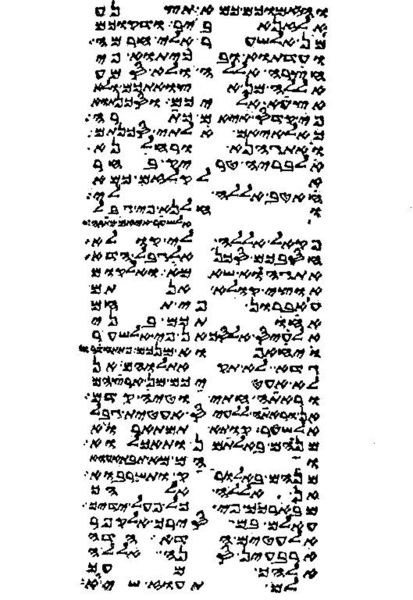

Samaritan Pentateuch

Transcription of a page of the Samaritan Pentateuch. The Samaritans - now barely more than 700 individuals - accept only the first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures (the "Torah") as revealed. Sometimes divergent textual lessons and the script itself in an uncial variant of the ancient Phoenician alphabet further indicate, at manuscript level, the centuries- old conflict between the Samaritans and the "Jews".

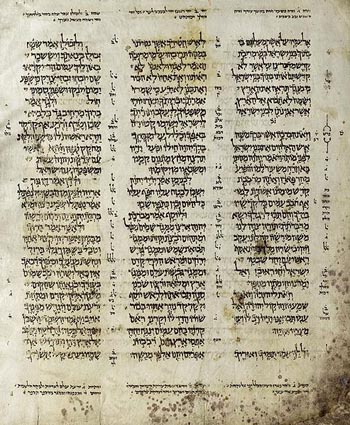

Aleppo Codex (10th century AD)

Page from the oldest codex, largely incomplete, of the Hebrew scriptures, drawn up following the system of Masoretic punctuation.

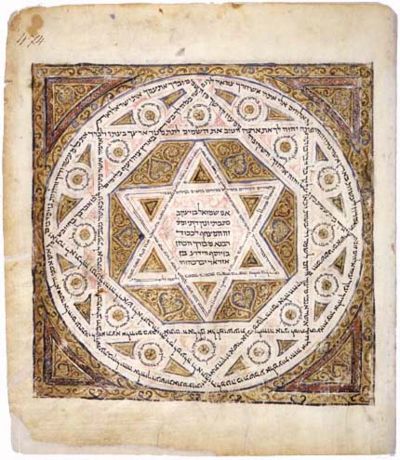

Leningrad Codex (about 1010)

Cover of the oldest complete codex of the Hebrew Bible. The name of the copyist, Shmuel ben Yakob, is indicated in the first line within the Star of David. The codex was probably transcribed in Cairo and sold to a purchaser residing in Damascus.

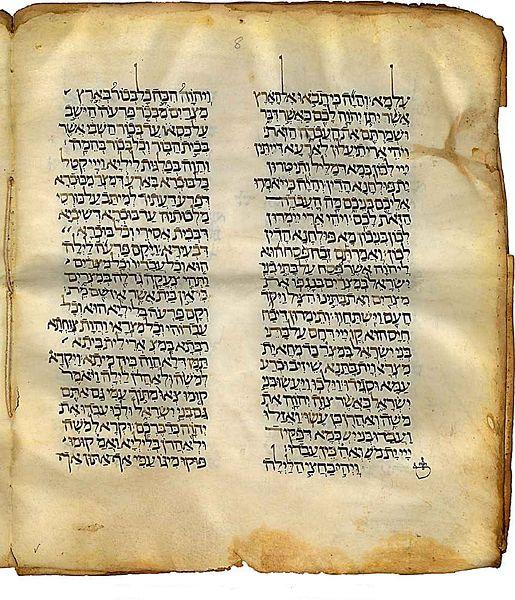

Targum

Page from a Targum, i.e., an Aramaic translation of the Hebrew Bible, from 11th century Iraq. The text given is Ex 12, 25-31. The two languages follow one another, often interrupting each other: first, the original Hebrew, then, the translation / interpretation in Aramaic, verse by verse.

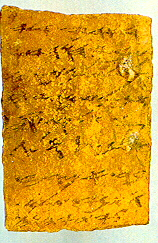

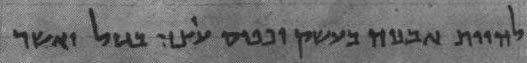

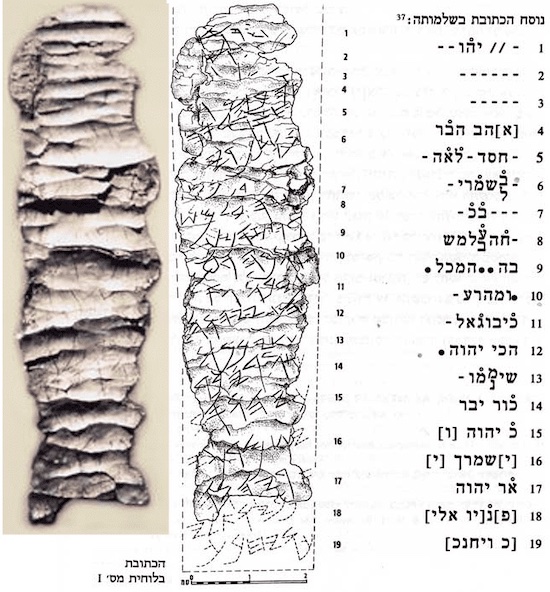

Two 'amulets' from Ketef Hinnom (7th-6th century BC)

Two little inscribed silver scrolls, often described as ‘amulets’ and

generally referred to as KH1 and KH2, were found in 1979 in Ketef

Hinnom, south-west of the Old City of Jerusalem, in the funerary chamber

25 of Cave 24. They are generally dated to between the late 7th and the

early 6th century AD (immediately before the destruction of Jerusalem

in 587-586?), although much later dating has been proposed

(4th-2nd BC). The hypothetical reconstruction of the last readable lines

from KH2, here reported in a transcription attempt in quadratic

alphabet, seems to denote the text of a blessing (ll. 16-19: YHWH “may

keep you, / may YHWH shine [his face / upon you]”) that will be echoed,

later on, in the formulas in Nm 6, 24-26 and 1QS col. II ll. 2-3.